- Home

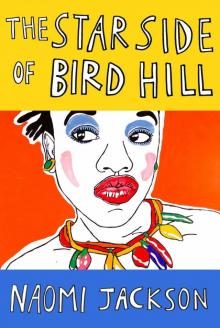

- Naomi Jackson

The Star Side of Bird Hill

The Star Side of Bird Hill Read online

PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Publishing Group

Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA • Canada • UK • Ireland • Australia

New Zealand • India • South Africa • China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, 2015

Copyright © 2015 by A. Naomi Jackson

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Excerpt from “Coyote Cry” from Prelude to Bruise by Saeed Jones. Copyright © 2014 by Saeed Jones. Reprinted with the permission of The Permissions Company, Inc., on behalf of Coffee House Press.

Excerpt from “The Long Rain” from Annie John by Jamaica Kincaid. Copyright © 1985 by Jamaica Kincaid. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

ISBN 978-0-698-15228-1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Summer 1989

Acknowledgments

Summer 1989

*

Bird Hill

St. John, Barbados

THE PEOPLE ON THE HILL liked to say that God’s smile was the sun shining down on them. In the late afternoon, before scarlet ibis bloodied the sunset, light flooded the stained glass windows of Bird Hill Church of God in Christ, illuminating the renderings of black saints from Jesus to Absalom Jones. When there wasn’t prayer meeting, choir rehearsal, Bible study, or Girl Guides, the church was empty except for its caretaker, Mr. Jeremiah. It was his job to chase the children away from the cemetery that sloped down behind the church, his responsibility to shoo them from their perches on graves that dotted the backside of the hill the area was named for. Despite his best intentions, Mr. Jeremiah’s noontime and midnight devotionals at the rum shop brought on long slumbers when children found freedom to do as they liked among the dead.

Dionne Braithwaite was two weeks fresh from Brooklyn and Barbados’s fierce sun had already transformed her skin from its New York shade of caramel to brick red. She was wearing foundation that was too light for her skin now. It came off in smears on the white handkerchiefs she stole from her grandmother’s chest of drawers, but she wore it anyway, because makeup was her tether to the life she’d left back home. Hyacinth, while she didn’t like to see her granddaughter made up, couldn’t argue with the fact that Dionne’s years of practice meant that she could work tasteful wonders on her face, looking sun-kissed and dewy-lipped rather than the tart her grandmother thought face paint transformed women into.

Dionne was sixteen going on a bitter, if beautiful, forty-five. Trevor, her friend and eager supplicant for her affections, was her age mate. Although Dionne thought herself above the things the children on Bird Hill did, she liked the hiding place the graveyard behind the church provided. So it was that she and Trevor came to the cool limestone of Dionne’s great-grandmother’s grave, talking about their morning at Vacation Bible School, and imitating their teacher’s nasal Texas twang.

“Accepting Jesus Christ as your Lord and Savior is the only sure way to avoid eternal damnation,” Dionne pronounced, her arms akimbo.

Trevor grinned, his eyes caught on the amber lace of Dionne’s panties as she walked the length of the grave.

“What do you think happens when you die?” Dionne asked Trevor.

“I don’t know. Seems to me it’s just like going to sleep. Except you never wake up. Why do you think so much about death anyways?”

“We are in a graveyard,” Dionne said. She traced the name of her ancestor while Trevor’s hand worked its way beneath her dress and along the smooth terrain of her upper thigh. She liked the way it felt when Trevor touched her, though she hadn’t decided yet what she’d let him do to her. She’d let Darren put his hands all the way up her skirt on the last day of school. But here, where girls her age still wore their hair in press and curls, she knew that sex was not to be given freely, but a commodity to ration, something to barter with.

Dionne squeezed Trevor’s wrist, halting his hand’s ascent, and then crossed her arms at her chest, which was testing the seams of her dress. After a few weeks of eating cou-cou and flying fish, her yellow frock fit snugly and rode up on her behind. Dionne was a copy of her mother at sixteen—her mouth fixed in a permanent scowl, her slim frame atop the same long legs, a freckle that disappeared when she wrinkled her chin. She hoped that one day she and her mother would again be mistaken for sisters like some of the flirtatious shopkeepers in Flatbush used to do back when her mother still made small talk.

Dionne’s and Trevor’s younger siblings, Phaedra and Chris, played tag among the miniature graves of children, all casualties of the 1955 cholera outbreak. Nineteen girls and one boy had died before the hill folks abandoned their suspicion of the world in general and doctors in particular to seek help from “outside people.” This was just one of the stories that Dionne and Phaedra’s mother summoned as evidence for why she left the hill the first chance she got. “They’re clannish. They wouldn’t know a free thought if it smacked them on the behind,” their mother would hiss, her mouth specked with venom.

Chris and Phaedra darted between the tombstones, browning the soles of their feet, losing track of the shoes they shook off on the steps at the top of the hill. They had become fast friends since Phaedra and her sister arrived from Brooklyn at the beginning of the summer. Phaedra was small for her ten years; even though they were the same age, her head reached only the crook of Chris’s elbow. Her skin had darkened to a deep cocoa from running in the sun all day in spite of her grandmother’s protests. She wore her hair in a French braid, its length tucked away from the girls who threatened her after reading about Samson and Delilah in Sunday school. Glimpses of Phaedra’s future beauty peeked out from behind her pink, heart-shaped glasses, which were held together with Scotch tape.

Hyacinth tried to get Phaedra to at least cover her head and her feet, saying that she didn’t need any black-black pickney in her house, and that, besides, good girls knew how to sit down and be still, play dolls and house and other ladylike games. Phaedra had never been one for girls in Brooklyn, and she didn’t see herself starting now. At the beginning of the summer, a whole gang of girls her age filed through her grandmother’s house to get a good look at her. They drank the Capri Sun juices Phaedra begrudgingly offered them from the barrel her mother sent. They chewed politely on the cheese sandwiches Hyacinth made and cut into quarters. Once they’d asked her all the basic questions (Where did she live in New York? What year was she in school? How old was her sister?), there was little left to talk about. They papered over the awkward silences by staring dumbly at each other and then promising to stop by soon. But by the time VBS started, none of them had come over again.

Phaedra knew that these friendships were doomed the moment she met Simone Saveur, the ringleader of the ten- and eleve

n-year-old girls because she towered over them and spoke with a bass the boys their age didn’t yet have in their voices. On her first and last visit to Hyacinth’s house, Simone Saveur sat down and started looking around, taking mental notes, collecting grist for the gossip mill. Because while Hyacinth could safely say that she had been into almost every house on Bird Hill, whether to deliver a baby or visit an old person who was feeling poorly, or just to sit for a while talking about who had died and left and been born, only a handful of hill women could say that they had seen Hyacinth’s house beyond the gallery where she sat with guests. All of them had at one point or another been invited to admire Hyacinth’s rose garden, which in her vanity she sometimes showed off, going on about how they bloomed, the insects that troubled them, her pruning techniques. It could be said that Hyacinth’s rose garden, which she tended to like another set of grandchildren, was an elaborate fortress whose beauty so thoroughly enchanted its visitors that they never questioned why they’d never been invited inside.

When Phaedra saw Simone looking around, she suddenly felt protective of Hyacinth and her house and everything in it: a pitcher and glasses with orange slices etched into them that had been around since before Phaedra was born, the open jalousies and the white curtains that lapped against the girls’ faces, the lovingly carved archway that separated the front room from the dining room, just barely fitting a dining table and a hutch, the pictures of Phaedra and Dionne and their mother, Avril, lining the walls. Where their apartment building in Brooklyn was marked with just a number, 261, Phaedra loved her grandmother’s house because of the question “Why worry?” written in blue script above the front steps. Everything in Hyacinth’s house had been touched by those she loved, and so it was Phaedra’s and Dionne’s in a way that their apartment in Brooklyn never would be.

Once, when there was a lull in conversation, Simone Saveur’s roving eyes settled on Phaedra. Simone tried to explain the concept of cooking a dirt pot, but Phaedra was not at all interested in cooking, not even for play, much less near her grandmother’s outhouse, which she was still too chicken to use, even when Dionne was taking forever in the inside bathroom, and she was dying to go. She knew she wouldn’t be playing any such game, or spending time with girls who thought this was a good time. Phaedra’s mouth corners turned down and soon everyone was saying their good-byes. Phaedra’s mother said that her daughter’s gloomy face could rain out a good time. In this case, Phaedra thought the force of her foul mood came in handy; it encouraged a quick end to what had been an uncomfortable, bordering on unpleasant, afternoon.

That summer, Chris and Phaedra were inseparable. Phaedra could barely trouble herself to remember the other girls’ names, having put them in the category of “just girls,” which was the same as dumping them into the rubbish bin of her mind. With Chris, there was ease to their play, a rough-and-tumbleness that she welcomed. Chris made Phaedra most happy by not asking her too many questions. Because while most of the Bird Hill girls were too polite to ask, she knew they most wanted to know about the thing she least wanted to talk about—her mother.

Phaedra liked to look at Christopher, who had the same sloe-eyed gaze as his mother’s, an ever-ready smile, and pink lips that made him seem more tender than other boys his age. Now she watched as he stuffed the stocky fingers of his eternally ashy hands into his pockets and surveyed the land below the hill, mimicking the firm stance he’d seen his father take in the pulpit.

From where they stood, Phaedra and Chris could see the fishermen’s boats at Martin’s Bay, the buoys bobbing up and down in the blue-green water. Further east, a riot of rock formations, vestiges of an island long since gone, jutted out at Bathsheba. It was Phaedra’s first summer in Barbados, and she wanted more than anything to feel the sand between her toes and to look at her feet through the clear-clear water. With its natural beauty, Barbados was far superior to Brooklyn; you were more likely to find a syringe than a seashell on the beach at Coney Island. She stood next to Chris, looking out at three rocks at Bathsheba that she and Chris had nicknamed the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. It was hard to explain, but she had a feeling, standing there, that she’d never felt before in Brooklyn, not that she owned these things, but that she was somehow part of them. When Phaedra went on a class trip to the Empire State Building and looked down at the city from 102 stories above the sidewalk, she didn’t have that feeling. The city was beautiful in its own way, but it wasn’t hers. She didn’t try to explain how she felt to Chris. What she most liked about their friendship was how much space there was for silence, the kind of quiet she’d never found with girls her age.

Chris turned his back to the sea, toward Phaedra.

“Touch it,” Chris said. He dared Phaedra to touch the grave of her namesake, her great-aunt Marguerite Phaedra Hill, who had died from cholera like the others.

“What if I don’t want to touch it?” Phaedra said.

“Then I’ll make you.”

Chris picked up an enormous rock and threw it at Phaedra. It opened her right temple in the same place where she had a dime-sized birthmark she had seen the Bird Hill girls looking at and straining not to ask about. The force of the blow knocked Phaedra off her feet.

The dull thud of stone against skull roused Dionne and Trevor from their mischievousness. Dionne ran to see what happened and gasped when she saw her sister lying prone on the grave, blood running down the side of her head.

“But what happen here?” Dionne said, breaking into the patois that usually lay hidden beneath her tongue.

“Why did you do that?” Trevor asked Chris.

“Mummy say wail woman head can’t break,” Chris said incredulously, over and over again, as blood seeped out of Phaedra’s head and commingled with the hill’s red dirt. Phaedra didn’t know what wail women were yet, but Chris leaned on those two words in a way that made it clear to anyone within earshot that being called one wasn’t a compliment.

Dionne took off up the hill with Trevor trailing behind her. She pressed her hands to her breasts to still them as she ran. (She’d already outgrown the bras that she brought with her; the homemade ones her grandmother had sewn lay unused at the bottom of her mother’s old chest of drawers.) She swept past the church and stopped at the rectory, a white clapboard house with a view of all the other houses on the hill.

Chris’s mother was where she always was, sitting on her veranda, listening to Jamaican rockers on her radio. The way that Mrs. Loving stared out for hours over the hillside, unmoving, reminded Dionne of her own mother.

“Phaedra got hit in the head by a rock in the cemetery,” Dionne blurted out before she made it to the veranda steps.

“Oh dear,” Mrs. Loving said. She went running behind Dionne, moving unexpectedly fast.

Hill women were busy putting laundry out on the line, picking okra for cou-cou, humming along to the grand old gospel of salvation on family radio. They formed a circle at the hill’s bottom, looking on.

“Christopher Alexander Loving, what have you done?” Chris’s mother bellowed as she walked toward him. Upon hearing his full name, Chris would usually have run to hide. Instead, he stood at Phaedra’s feet, shading her from the noon-high sun. He looked down at Phaedra, transfixed, mumbling to himself.

Mrs. Loving took Phaedra’s head into her lap and let the blood soak her dress. She slapped gently at her face. “Come now, child, don’t let sleep take you.”

Finally, Phaedra opened up her eyes. “Mommy, what happened? Everything’s starry.”

“Hush, child, hush. Mummy’s not here, but she soon come,” Mrs. Loving whispered.

Phaedra looked up at Chris’s long shadow and then at Mrs. Loving above her. She was struck then, for the first time, by the heaviness of her head, the aching there, and the oddness of someone other than her mother trying to comfort her.

DIONNE HATED MOST THINGS about Barbados, especially the weather. She disliked the cool damp of the

mornings, followed by the unforgiving heat and insistent afternoon rains that drowned any hopes of going outside. During the long, wet days when she was forced to keep watch over her sister, Dionne felt like one of the sick and shut-in from the church bulletin. Maybe this is what growing old was like, she thought. Maybe the world gets smaller and smaller until there’s nothing but the walls around you to show you where you end and the rest of the world begins.

The weather was just one thing on a long list of gripes that Dionne kept in her head, and occasionally wrote in the margins of the fashion magazines she’d brought with her from Brooklyn. Chief among her complaints was that there was nothing to do to entertain herself. The days just seemed to drag on and on. She sometimes looked up at the clock thinking an hour must have passed, when in fact it had only been a few minutes. And while she always resented the long list of things she had to do back in Brooklyn—prodding her mother, Avril, to get up and bathe each day, making sure Phaedra was dressed and her hair decently combed, cooking dinner and packing lunches for herself and her sister—in Barbados she felt like she had been demoted back to childhood, asked to put on a pair of too-small shoes by being responsible only for herself.

Hyacinth believed that idle hands were the devil’s playground, and so she gave the girls chores to do and signed them up for not one but two sessions of Vacation Bible School. Still, Dionne felt a restlessness welling up in her. Dionne thought Bird Hill was provincial, far too small a stage for a girl like her. There was a flash of excitement when a talent scout for the Miss Teen Barbados pageant came to Bird Hill. For a brief moment, something like joy washed across Dionne’s face when the other girls pushed her forward, saying that she would surely win. But when the scout heard her accent, the woman—whom Dionne later pronounced both too fat and too ugly to be scouting for a beauty pageant—asked whether she was of both Barbadian heritage and Barbadian citizenship, and she’d had to admit that she was in fact an American citizen. Just like that, Dionne’s dreams of emancipation from the lot of the fatally dull girls in Bird Hill were dashed.

The Star Side of Bird Hill

The Star Side of Bird Hill